John Milton was a significant civil servant – the chief translator of diplomatic documents for the English Commonwealth of 1649-1660 – when, already blind, he began to dictate Paradise Lost. When he published it in 1667 he was a political outcast and widely reviled after the reversion to monarchy, but he was rapidly hailed as the author of what many have regarded as the greatest non-dramatic work in the English language.

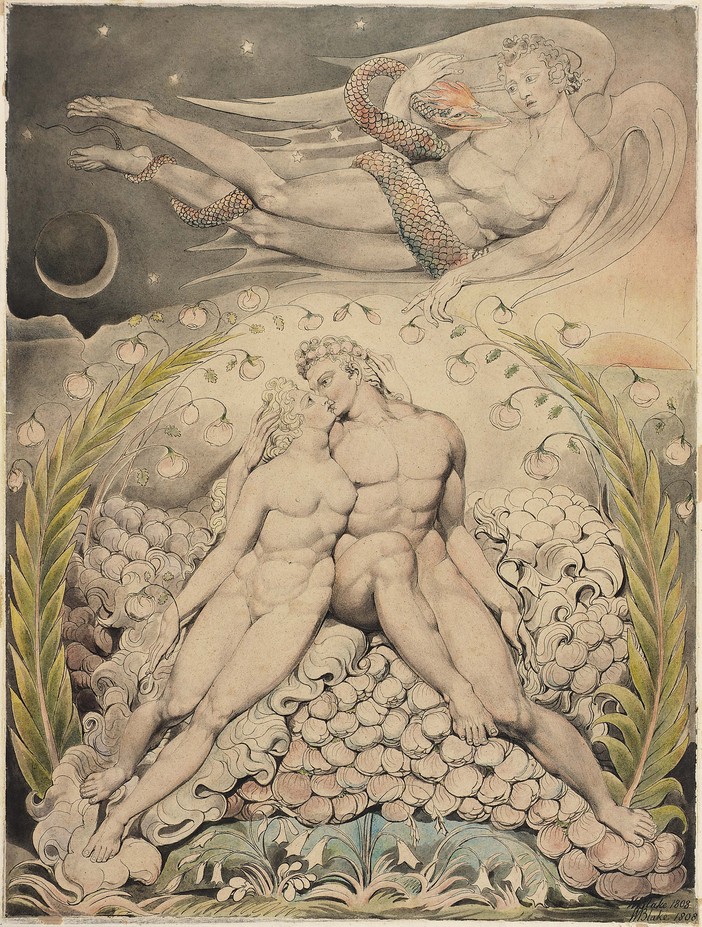

Paradise Lost tells the story of the Fall of mankind in the Garden of Eden, and before it, the rise of the rebel angels in heaven, led by Satan, and their defeat and casting into hell. Milton’s rewrite of the Book of Genesis in the Bible is extensive; to call it daring is an understatement. Into the poem was compressed all of Milton’s remarkable learning, his immense poetic gifts, and many of his unusual and often idealistic view of human free will, the origins of evil, the relations between the sexes and how mankind relates to God.

The best way to read Paradise Lost is to go carefully from end to end, book by book. There are many wonderful editions: we recommend Kerrigan, Rumrich and Fallon (2008). All the information to do with the text, brief details of Milton’s life, and historical background will be found there. An important new, deeply reflective biography is McDowell (2020) but that only goes halfway to 1642, so you may want to read Von Maltzahn (2009).

There is a huge and ongoing cultural debate about Paradise Lost: battles between those who think Milton was in rebellious sympathy with Satan against a tyrant God, and those who see a final defense of God and his ways; between those who admire Milton’s epic poetic style, and those who see flaws; between those thrilled by the poet’s intellectual daring, and sceptics who see a more orthodox figure; between an old school misogynist and a poet decidedly on the side of independent female consciousness; between a poet in tune with the birth of modernity and the scientific revolution, and those who see a retrospective poet obsessed with antiquity. There are useful extracts of many of these views in Teskey (2020), while Achinstein (2017) represents a recent focus on Milton’s hopes for humanity in Paradise Lost.

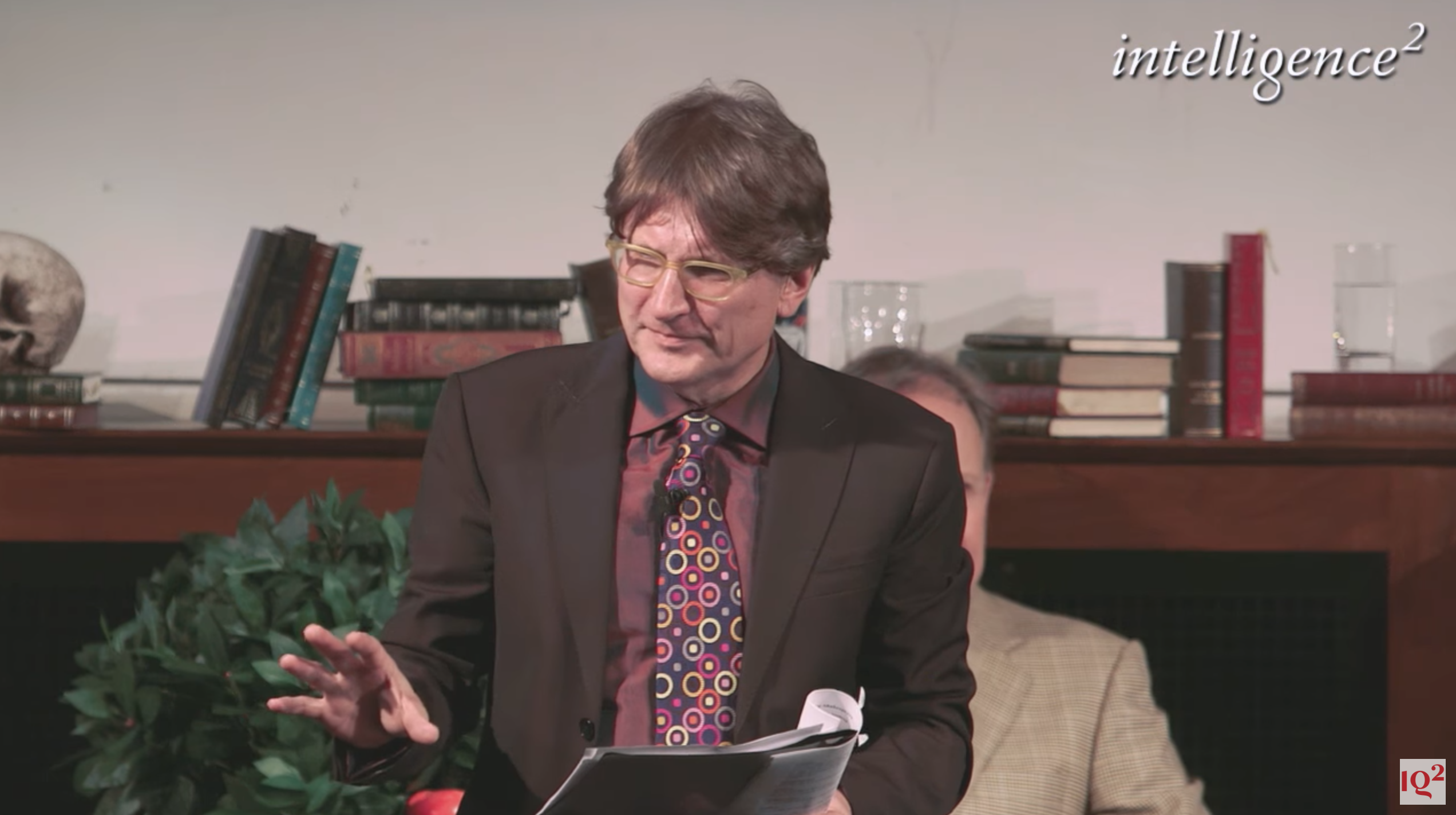

You can study Paradise Lost and much more about Milton at the estimable Dartmouth College Milton Reading Room. Readings of Paradise Lost are popular, often the whole poem in one go (takes about 12 hours), and some of this is registered on the internet, where you will also find a defense of Milton against Shakespeare involving our own Nigel Smith, with readings by distinguished actors and actresses.

Text

Milton, John, Paradise Lost in The Complete Poetry and Essential Prose of John Milton, edited by William Kerrigan, John Rumrich, and Stephen M. Fallon 283-630. New York: Modern Library, 2007.

Biography

McDowell, Nicholas, Poet of Revolution: The Making of John Milton. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020.

Von Maltzahn, Nicholas, “John Milton: The Later Life (1641–1674)”, in Nicholas McDowell and Nigel Smith, eds., in The Oxford Handbook of Milton. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Criticism

Achinstein, Sharon, “Milton’s Political Ontology of the Human,” ELH, 84 (2017), 591-616.

Teskey, Gordon, ed., “Criticism” in John Milton, Paradise Lost, ed. Teskey. New York: W.W. Norton, 2020, 395-536.

Shakespeare v. Milton

A defense of Milton against Shakespeare involving our own Nigel Smith, with readings by distinguished actors and actresses